Mica — The most comforting fact about life for me is impermanence.

Nothing lasts forever. Not the good, not the bad.

This fact comforts me through all my depressive episodes and makes me appreciate my happier moments with a pre emptive nostalgic ache in my heart, knowing that the moment is made even more precious by its impermanence.

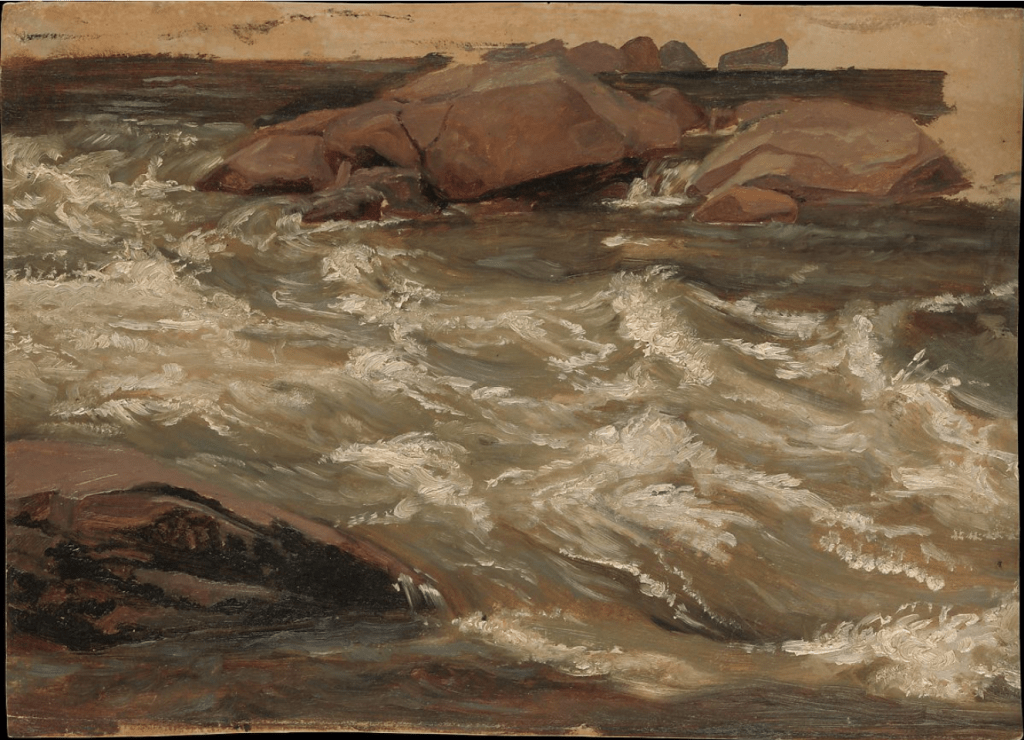

When friends ask me how I am doing I often respond with “ebbing” or “flowing.” Life ebbs and flows. Cycles through ups and downs, cycling through the seasons. Maybe because I am a summer baby I feel myself flow the most in the spring and summer months and ebb the most during winter months.

I imagine myself to be a river in a forest. Freezing over, slowing my drift through the winter months and then thawing out and rushing down stream during the spring and summer months. Awakening as if from a big sleep. Of course, I haven’t been asleep all winter. Yet, I can’t help but feel part of me has.

I’ve grown accustomed to this cycle in myself. Letting the cold and grey of the winter landscape seep into my bones and psyche. I reason with myself. “This always happens, you’ll be better in the spring.” As if my insides will thaw with the weather and I will feel again. Even writing this, I feel the anticipation of spring and summer in my body.

The yearning for warm weather,

fresh air,

sleeping with the windows open,

longer days,

bare legs.

Of course, this heavy dependence on spring and summer has its drawbacks and leads to even more self loathing when I ebb in the spring and summer months. How can I be upset when it’s sunny and beautiful outside? Aren’t I supposed to be flowing?

But that’s not how ebbs and flows work. That’s not how life works. Not in me, not in nature, not for anyone. Impermanence is the most perpetual of cycles.

It’s like the famous Japanese Buddihist concept of wabi sabi: nothing lasts, nothing is finished, nothing is perfect.

Such is life, so are we.

Chelsea — Reminding myself that impermanence exists is difficult. My dad died when I was sixteen, and what I took from that was a lesson I’ve been hard pressed to give up. The things that happen to us are fixed, and in turn, we are fixed to them.

Prior to forming this worldview, my dad was always telling me change is the only constant. Beyond a strange premonition, what he failed to clarify was this only applies to the human experience, not the events that occur to them. I wouldn’t believe my father’s death could remain fact. He trained me to believe change is constant. He trained me to believe in impermanence. But I was affixing impermanence to the wrong part of this equation. I wanted to believe I had the power to change the thing, rather than accept I had been changed by it. And so I created stories to stay fixed in time, to keep him alive.

I believed for many years he was a spy. He had to make it seem like he’d gone and died. But he’d be back. Only I could see this body was nobody, bloated on the stretcher, broken from CPR. It was a mere facsimile. I would walk Chicago in anticipation. He’s going to be waiting for me at the end of this block. He will visit me at the coffee shop where I work, disguised, and give me a nod. Then, I’d know.

He would answer his phone, finally. His numbers indelibly scratched into my brain. I would dial them over and over convinced he would pick up. When finally the ringing changed to beeps and we’re sorry you have reached a number that has been disconnected or is no longer in service. That bit of impermanence was harder to swallow than almost any. And even though the gift of suspended disbelief I seek has been shortened from a few rings to a millisecond of silence before the unbearable tone and automated message plays, I still hold my breath and call.

Another one, I’d enter my apartment coming home from the bar and he’d be sitting there telling me he had to go away to protect me and my mom. He’d tell me he was sorry. He would make me coffee even though it was late. He would sit in a chair while I sat on the kitchen counter and he would say look, it’s just like old times. I would stare down in my lap, swing my legs, and take a sip. I’d be comfortable under the blanket of his watch. I’d be comfortable on my counter, in my apartment. I’d be comfortable in myself for the first time in a long time. Then I’d look up without a doubt, knowing he’d be there engaged in a simple movement of life. Blowing air over his hot coffee. Taking a sip. Exhaling.

When I was young my family went to church a lot. Fourth Presbyterian. It’s old and beautiful and sits right at the beginning of Michigan Avenue across the street from the John Hancock building. Being part of the Presbytery of Chicago (or the midwest, I don’t know), we had access to a camp in Saugatuck, Michigan. The church would plan weekend sessions where members could sign up and take their families. We’d all go and stay in cabins high up on a dune right above the shores of Lake Michigan. At night, as we fell asleep, we could hear the waves. I think this is where my love of wooden-framed screen doors with tiny metal handles originated. The ones with creaky coiled springs and a decided slam.

I was around nine during one of the times my family and I went. The dinner bell had rung – everyone ate every meal together – but I decided to sneak away and sit at the top of one of the dunes. The sun was setting over the lake, and with everyone at dinner it was quiet. I took off my shoes and wiggled my fingers and toes deep into the cool sand. I watched. I remember thinking if there is any evidence of God in this world, this has got to be it. Then my dad found me. He didn’t ask what I was doing. He accepted I was there, that I had stayed behind for a reason. He told me it was time to come in for dinner. And we walked together to the mess hall.

The point is, though, the camp was eventually sold. It now belongs to a large development company that will build luxury cabins for wealthy Chicagoans looking for weekend getaways. How can a person stand so much change? Is there anywhere I can drop my anchor that won’t be ripped away? Our people, our homes, our landmarks are impermanent. I can’t stand it, and yet I have to. The things that happen to us they mark us. The deaths, our memories, the good, the bad, sunsets over a dune, the razor-slit eyes of my father in a casket. They mark us. They are fixed to us and we to them, but I’m learning we are not fixed by them. There is a spring and a summer and a fall and a winter, and I want to meet them. My friend has a baby, and I want to watch him grow. We carry on, carrying these things that have happened. More will surely come to pass. What else can we do but nod and delicately add it to our load?